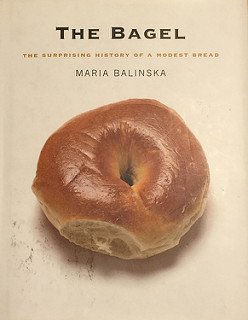

Sometime this week I finally finished reading The Bagel: The surprising history of a modest bread, by Maria Balinska. I was surprised at how long it took me to get through the book, considering it’s a rather small-format book with only seven chapters (though it also includes some front and back matter as well). One of the clues I ignored was that the book was published by the Yale University Press, a small indication that this would be more of a scholarly/historical work than a little light reading about East Coast noshes. (Another clue would have been the fact that the book, though compact, has more than 200 pages.)

This book is not a light and amusing food memoir; it’s definitely an elaborate and almost exhaustive food history of a very specific example of food. At times I thought it might be easier to borrow my mother’s copy of Poland by James Michener. That, however, was only when I was finding myself steeped in accounts of Polish military history. When the book moved on to documentation of the struggles of Jewish bakery unions in New York City, at times I thought I could switch over rather easily to The Autobiography of Mother Jones.

That being said (and rather too snarkily, which the book and the author do not deserve), a book such as this one is a labor of both love and scholarship. The author clearly has a personal and familial interest in bagels, but also is a Princeton graduate and spent a year in Krakow studying Polish language and literature. She travelled quite a bit, did extensive research, and conducted many interviews in order to bring this book together. I learned a tremendous amount about the religious, cultural, and historical events that led to the Continental and American popularity of the bagel.

What did this book teach me, as a baker, about bagels? Well, considering that a 200-page bagel history doesn’t contain a single bagel recipe, I learned a lot about the preparation methods, the texture, and the change in the substance and meaning of bagels from the era of slave-labor handmade production in the underbelly of NYC to the era of the pre-sliced, flash-frozen, mass-market bagels I grew up eating. (Lender’s, I’m talking to YOU.)

These days, a bagel represents a sandwich bun with an ethnic history. It might be plain, a little seedy, or quite cheesy. But less than a century ago it was a symbol of multiple facets of that ethnicity — nourishment, tradition, spirituality, and the economic struggles of generation upon generation. It was a very Jewish history, which seems to have been lost somewhere within the mass-marketing of the bagel to WASPy Midwestern America. We don’t want to call anything Jewish, so it becomes a “cultural” thing, an “Old World” thing, or a “New York” thing. All those things belong to the “other” and not to whatever it is that represents “us.” I suspect that we speak in code so that eating “Jewish” food doesn’t make us become Jewish any more than naming our children Sarah, Leah, Rachel, Hadassah, Jacob, Joshua, Isaac, or Isaiah makes them Jewish when we consider the names to be “traditional” or “Biblical.” We grant the name but deny the meaning.

I digress. But perhaps I don’t. The bagel’s history is a political one, and it’s also a religious and ethnic one. I probably wouldn’t be baking and writing about bagels if I didn’t know a Jew who wanted access to proper bagels. Bagels are fine at worst and terrific at best on their own, but they mean something more to Jews. When I bake bagels, that’s the something I’m trying to provide. I hope that it shows.